Subjects, Consumers and Citizens

This week I found myself rolling my eyes at a proposal to issue "receipts" to every New Zealander showing what their tax dollars had purchased.

These sorts of ideas pop up regularly.

We've been trained to think about "ratepayer spend" and "taxpayer dollars".

This proposal was simply another in a long line that is problematic for two reasons.

Firstly, the evidence is that that these solutions don't actually increase people's connection to politics, governance or government.

Secondly - and more importantly for our purposes - the very idea comes from a particular worldview that damages our society.

The three stories - subjects, consumers and citizens

Jon Alexander and Ariadne Conrad's book Citizens: Why the Key to Fixing Everything is All of Us came across my LinkedIn feed thanks to Freda Wells.

The core idea of the book is simple. (And while I'm always suspicious of simple explanations to complex systems, they can still help us to navigate that complexity.)

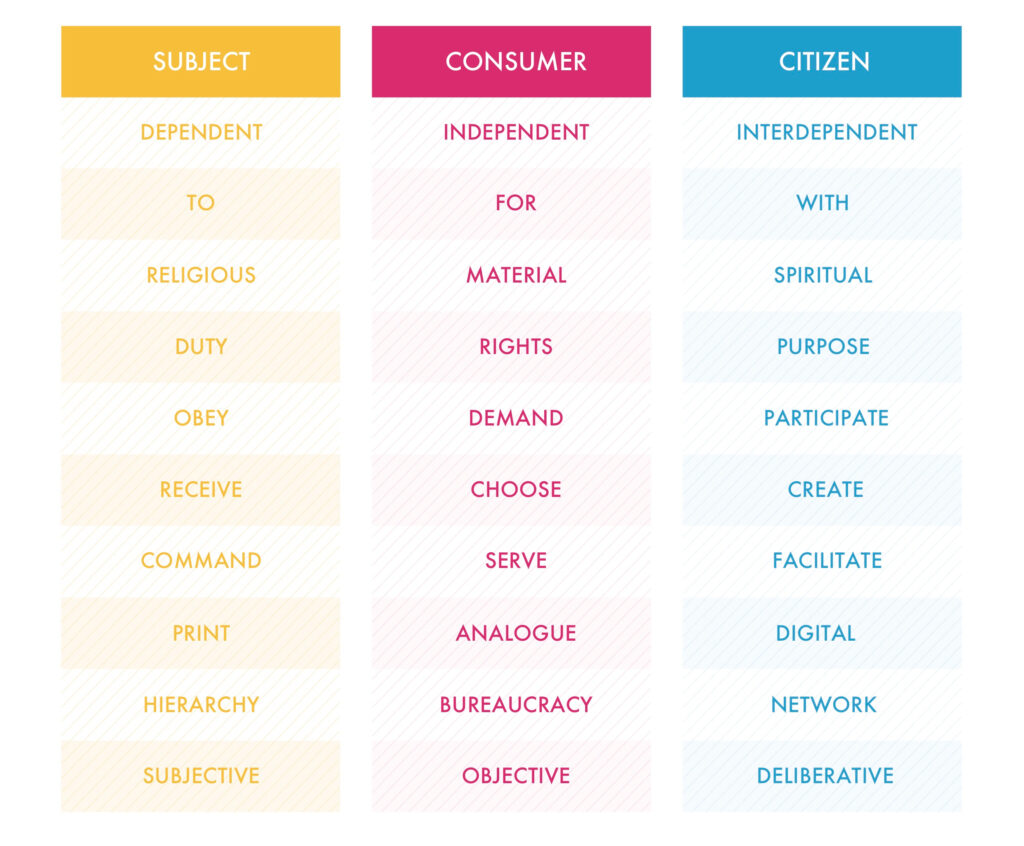

The authors suggests there are three dominant stories about our relationship as individuals to our collective society.

For centuries, the dominant story of many societies has been the story of the subject.

In this story, we the people are loyal subjects of our kings, queens, emperors and chiefs. Our royalty is somehow better than us, and uniquely suited to rule. (Until we realise they are useless and we overthrow them for another ruler.)

This story doesn't just show up in our distant past. It's present in many of our organisations too. We look to inspirational leaders to provide vision and clarity, if only we set aside our own power and agency.

But in the 1900s another story emerged: the consumer story.

In this story, we the people are individually powerful and can influence our society through our individual choices.

Put simply, buy the right things and we will be happy.

You can see how this was a powerful story for people who had been subjected to another's dominant rule for so long.

The language of consumerism dominates today - even in areas relating to the public good.

Sick people are "healthcare consumers".

Anxious young people are "service users".

Homeowners are "customers" of their local council.

But the limits of consumerism are clear. The story doesn't work because we cannot always shop around. We cannot take our custom to a different government department to get a better deal. There is only one WINZ.

At a deeper level, the consumer story prioritises individual action over collective action. And it ignores the larger underlying causes that exist further up the chain.

But there is a third story - the story of citizens

Being a citizen means recognising our power to change the systems that we humans have created.

Unlike the citizen story, this story tells us that we shouldn't just accept inadequate systems as they are. Instead, we can take individual and collective action to change those systems.

To be clear: you can still consume, you just don't need to be a Consumer.

The power of the book is that it gives us a new frame of reference for understanding events and choices.

Next time you hear or see a policy choice or hear about a new idea - ask yourself:

What story might be shaping this?

Next time a leader in your organisation shares a proposal with you - ask yourself:

How might this proposal change if we start with a different story?

These are important questions.

After all, words create worldviews, and worldviews create worlds.